The Ground Truth for Visual User Interfaces

Browser accessibility is almost always a nightmare and even the world’s most popular websites like Amazon are a total pig to navigate without sight due to the overwhelming amount of content. New Computer Use Agents could be a game changer for blind users

Earlier this month, Microsoft released an open source AI model, Fara-7B, one of a new class of agentic models known as Computer Use Agents (CUAs). CUAs drive a computer’s visual user interface as if they were a human user, sending mouse actions and keystrokes to an application and then interpreting the application’s visual output.

Right now Fara-7B is a research project and not production ready, but CUAs are a very active development area for all the major AI labs so we should expect dramatic progress in this area during 2026.

The most ubiquitous application that these models will drive is the common or garden web browser, for doing everything from searching out content and online shopping to accessing gmail, LinkedIn and all the other services that expose a web interface.

At the end of this post, there is something very interesting from an accessibility point of view in the emergence of these agents, but first some accessibility background.

Over the years, conventions have arisen for web page layout. For example there is usually a navigation section at the top, and at the bottom are all the legal and regulatory bits no-one reads, like the modern slavery policy, the privacy policy and conditions of use.

But there are no hard and fast rules for this structure and there is much less standardisation on the interesting page content itself which is surrounded by all this template guff.

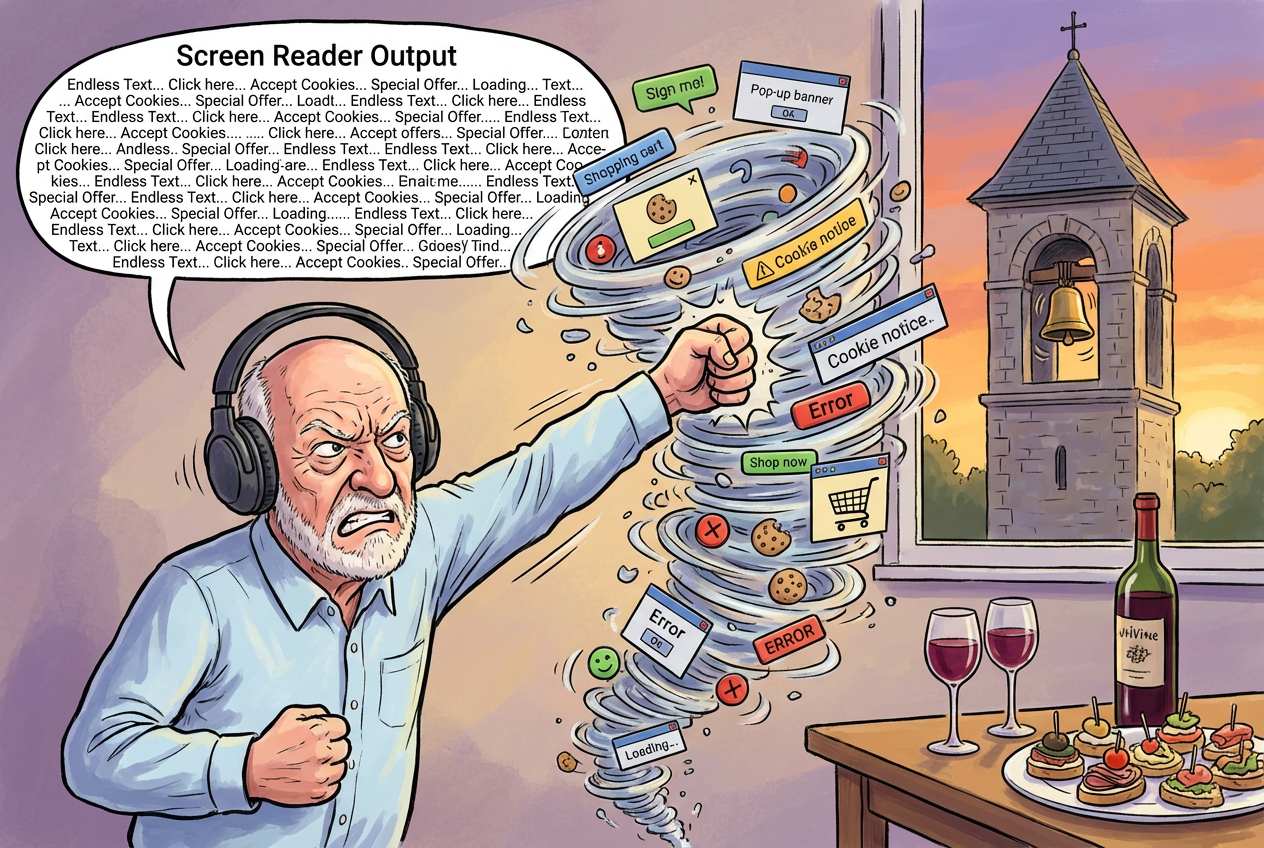

If I had a more positive mindset I’d treat web browsing as a sort of neural calisthenics – sudoku for the blind. But as it is, making a purchase from an unfamiliar site or just getting directions to a new restaurant is likely to burst blood vessels.

And even for sites I regularly visit, the never ending addition of new features or offers I never wanted repeatedly breaks my personal sequence of arrow keys, tab keys and more arcane shortcut keys for the simplest task. After 25 minutes just now failing to order some basic earphones on Amazon, a website I’ve been using for over 20 years, I was only saved from punching my laptop by the church bells outside my window melodiously chiming wine o’clock. For the masochists amongst you, this audio clip is the first few seconds of screen reader output when I clicked on the link to the search results.

The speech rate in this clip is the normal speed at which I listen to my screen reader, although I have friends who have theirs cranked up significantly faster. The output is, as you’ll hear, incredibly verbose, and this is just the preamble to the page.

Website accessibility is a fiendishly difficult challenge, and even websites that conform to all the accessibility guidelines, are often impenetrable by blind users.

Accessibility is in theory provided by a combination of an Accessibility Object Model exposed to screen readers by browsers and specific accessibility elements and tags coded into individual web pages. These mechanisms, combined with rigorous adherence to accessibility guidelines and comprehensive accessibility testing are supposed to make the web accessible to all. Sadly the reality is far from the ideal.

A few months ago I read that early AI browser agents use these accessibility mechanisms to understand web pages. Excellent news because this future mainstream use of the mechanisms should ultimately lead to more comprehensive implementation and therefore better accessibility.

But here’s the interesting thing, explicit in Microsoft’s Fara-7B announcement, which will I suspect also apply to CUAs released by other AI labs. Fara-7B does not use any of the accessibility mechanisms to understand a web page. Instead, Fara-7B relies totally on using computer vision techniques to recognise the visual elements of the page pixel by pixel and build up a detailed understanding of the page. This will logically be exactly the same understanding a sighted user would build up, using the ultra fast and super accurate visual cortex of their own brain. If a sighted user cannot see it then it is not part of the visual interface, and if a sighted user can see it then it is the visual interface.

Whether this is a good or bad thing for web site accessibility depends on whether there is a widely available CUA with a comprehensive accessible interface. I’m betting on that interface being conversational voice. The challenge will be ensuring that the widely available CUAs do not default, for example, to interfaces that use conversational voice for input and visual summarisation for output. That would be A Bad Thing, because I would then have to use a screen reader to interpret the output of the conversational voice agent. That would be just another turn in the never ending dance of one step forward and one step backward between technology and inclusivity.