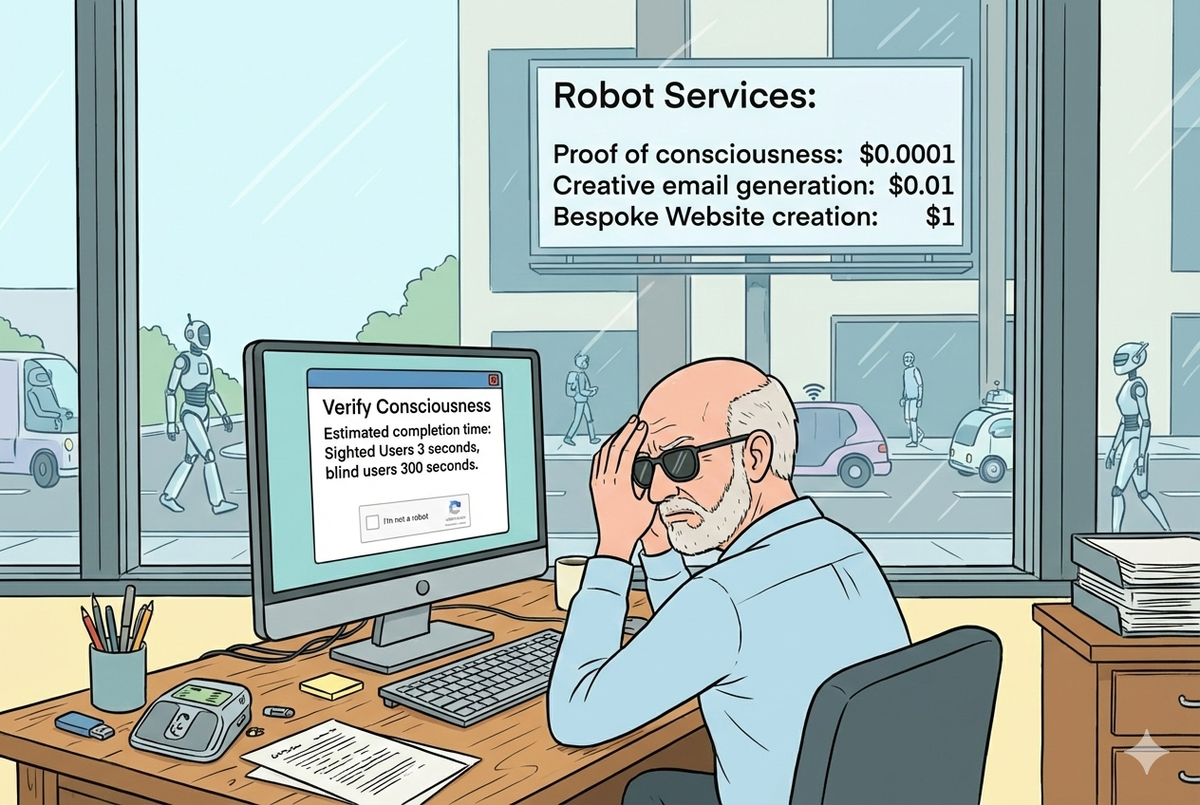

'I am not a robot': Wilfully and pointlessly inaccessible by design

Captchas aimed to block bots from scraping sites and creating fake accounts. Now bots outperform humans at them, while legitimate agents make blocking pointless. Vision-impaired users suffer as collateral damage—but new techniques may fix this.

The anachronistic stupidity of website captcha dialogs for distinguishing humans from scammy bots is deliciously highlighted by the tick box that starts the accessibility shitshow. ‘I am not a robot’ causes my heart to sink along with the hearts of many other vision impaired users. As AI Computer Use Agents come along in leaps and bounds, they obviously have to lie about their robotic status by ticking the box and then successfully completing the image or audio challenge. The latest AI agents can already complete these challenges better than most humans and neither the user nor the website operator want a personal AI agent to stumble at this first hurdle.

The tick box would be better phrased as “Give me a task that high volume scammers or scrapers cannot afford to solve”.

That was always the intent of captcha dialogs. They started with images that are clearly discriminatory against vision impaired users, so audio recognition was added as an alternative. But to fool speech recognition software the audio was often so distorted to be incomprehensible by vision impaired users.

The audio has become significantly easier to understand over the past couple of years for a couple of reasons:

- The distorted audio no longer hinders and actually assists state of the art speech recognition.

- Vision Impaired lobby groups took legal action against websites with unreasonably challenging audio fragments.

But even with the clearer audio, the captcha dialog is an accessibility nightmare. The way these dialogs pop up and then disappear very often confuses screen reading software. So my laptop becomes silent, expecting me to telepathically tab in or out of the captcha area. The user flow is trivially obvious to a sighted user with a mouse but akin to pinning the donkey’s tail for me. This blindfolded game provided hours of harmless entertainment at children’s parties before the advent of television, videos or the internet. But when you’re signing up to a new website, buying an airline ticket or completing a customer survey, the fun wears thin extraordinarily fast.

Signal based captcha is a relatively recent innovation for low friction human identification through pauses for thought, wiggly mouse movements or other non-robotic behaviour. The browser resorts to the good old fashioned, high friction image/audio challenge if the indirect signal does not look typically human.

And guess what? Blind users with screen readers and keyboards don’t use websites like typical ‘mouse first’ sighted users, so we’re back to the old fashioned fallback for precisely the group of users who have always found that approach most painful.

Surely there must be a better way? And hurrah, there actually is a solution based on proof of work, which is 100% blind friendly, because it is totally invisible for everyone. This is really elegant borrowing from the cryptographic proof of work which underpins bitcoin. The idea is that discovering (i.e. ‘mining’) a new bitcoin can only be done by finding a new, unique and very long sequence of numbers that conforms to the magic key. There is no way to cheat as a bitcoin miner; you just have to crunch the numbers for literally months with a very high performance computing rig. Hence the expression ‘proof of work’. A bitcoin is worth approximately $100,000, so miners are incentivised to do shed loads of work to find one. In contrast, the value to a scammer of a solved captcha is only a fraction of a cent.

On 2captcha, akin to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk for outsourcing micro-tasks to human workers in low cost economies, the going rate for a bundle of 1,000 captchas is $1-$3 (i.e. 0.1-0.3 cents per solved captcha). This sets a limit on how much work is a big enough barrier to mass scammers using bots to create thousand of new accounts or do the other things that website owners are trying to prevent with captchas. If the scammer can pay a human 0.1 cents per solution to solve the captchas, that is what they will do if the proof of work uses more than 0.1 cents worth of electricity.

Compared to mining a bitcoin this is like a teaspoon of salt versus all the sand on all the beaches in the country . So having the browser solve a relatively simple cheat-proof crypto puzzle while the user is deciding what to do next is good enough - the user doesn’t even realise it’s happening.

This might introduce unacceptable delay on low power devices, but that delay is only unacceptable if your normal path is 2 seconds eyeballing a trivial task. If the default delay is 15 minutes of frustration, swearing and failure to find the captcha dialog then a minute of quiet contemplation while my browser proves I’m human feels like a real win. We do need to overcome inertia in the massively distributed web, with millions and millions of site owners – then “Voilà!” – captchas will disappear as one utterly unnecessary but real and painful barrier to blind web access. And this small triumph will have come about partly because AI got better than humans at proving it is not a robot.